Whoops.

So apparently the majority of the papers I have first authored at this point in my career are about stars. I've even published an entire paper on just two stars (or one, depending on how you count ... the idea that "a binary star" is really two stars hasn't fully infiltrated the nomenclature, it seems). It took a lot of doing while writing this paper to figure out just why anyone would care about a bunch of variable stars; for the paper I wrote about dust structures at other galactic center, the explanation of why the topic is interesting was much easier to sink my teeth into (though "centers of galaxies are interesting because I get to look at pretty galaxies" is apparently not a sound argument).

This paper is about "variable stars near the Galactic center," where "near" is defined as within about 2 pc (about 6.5 lightyears) of the supermassive black hole, Sgr A*, at the Milky Way's center. I've put a completely gratuitous picture of the field below; the yellow X marks where Sgr A* is, the dots are on variable stars, and the cyan dots are the stars I actually talk about in the paper. The bar denoting how much 30'' is corresponds to 3.6 lightyears. This field of view (i.e., how much we can see) is larger than many of the stellar variability studies near the Galactic center, but still small enough that we can basically assume that all of the stars we are looking at are pretty close to Sgr A*. The metric I usually keep in mind is that the size of a resolution element when looking at nearby galaxies with the Hubble Space Telescope is 1–15 pc. In other words, this entire field of view would look like just a few bright pixels if it were in another galaxy.

Or, it would look like a few dark pixels, if we were looking at the galaxy edge on. And, because we are in the disk of the Milky Way, we are looking at the Milky Way edge on. This is why things like exactly where the center of the Galaxy is and the fact that the Milky Way is a barred galaxy weren't known until recently. Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way have lots of gas and dust in them between all of the stars (so it is called the "interstellar medium," or ISM). This dust absorbs light, so it is very difficult to see stars near the center of the Galaxy (which is thought to be about 7600 pc away these days). Because dust absorbs more blue light than red light, something sitting behind a whole bunch of dust looks redder than it intrinsically is. This is why absorption due to dust is referred to as "reddening," and why we have to look at infrared wavelengths to be able to see stars near the Galactic center.

The paper is essentially just a list of the 110 variable stars we identified; about 90 of these are new (depending on how you count). "Look, here's a list of variable stars and their light curves" doesn't make for all that interesting a paper—even if most of the list is new—so I put a decent amount of effort into trying to cross-correlate our catalog with known sources (known variable stars, of course, but also X-ray and radio catalogs) at the Galactic center. Many of our variables that matched up to other sources are fairly well-known, and even have names. One of these stars was IRS 16SW, which we wrote a paper on last fall, but I think the most interesting of the previously-known objects in our catalog is IRS 10*.

This is our light curve for IRS 10*; the vertical axis is the K-band magnitude (remember, smaller numbers means brighter!) and the horizontal axis is in days. What makes this object actually interesting isn't that its brightness changed so much, but that by poking around in the literature (literally—remember that big pile of papers?), I found that there are several stellar masers and a bright X-ray source sitting at pretty much the same location. When I started this project, I definitely didn't know anything about masers, so here's pretty much all you need to know: (1) they are like lasers, except at radio frequencies, and they actually amplify light instead of merely letting it coherently oscillate; and (2) masers associated with stars are generally associated with stars with lots of gunk around them (the stuff actually doing the masing); these stars are usually "asymptotic giant branch" (AGB) stars, which are basically old stars that are busy shedding their outer envelopes. The idea that IRS 10* is an AGB star isn't all that exciting; what is exciting is that AGB stars are not bright X-ray sources, so if the nearby X-ray source actually is associated with IRS 10*, then it probably means that IRS 10* has some dead companion (like a white dwarf) which is accreting mass from the AGB star. (If the X-ray source isn't associated with IRS 10*, the question then becomes: what can cause such a bright X-ray flux and not vary at these wavelengths?)

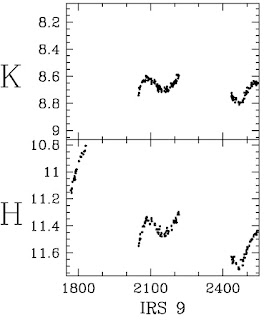

This is our light curve for IRS 10*; the vertical axis is the K-band magnitude (remember, smaller numbers means brighter!) and the horizontal axis is in days. What makes this object actually interesting isn't that its brightness changed so much, but that by poking around in the literature (literally—remember that big pile of papers?), I found that there are several stellar masers and a bright X-ray source sitting at pretty much the same location. When I started this project, I definitely didn't know anything about masers, so here's pretty much all you need to know: (1) they are like lasers, except at radio frequencies, and they actually amplify light instead of merely letting it coherently oscillate; and (2) masers associated with stars are generally associated with stars with lots of gunk around them (the stuff actually doing the masing); these stars are usually "asymptotic giant branch" (AGB) stars, which are basically old stars that are busy shedding their outer envelopes. The idea that IRS 10* is an AGB star isn't all that exciting; what is exciting is that AGB stars are not bright X-ray sources, so if the nearby X-ray source actually is associated with IRS 10*, then it probably means that IRS 10* has some dead companion (like a white dwarf) which is accreting mass from the AGB star. (If the X-ray source isn't associated with IRS 10*, the question then becomes: what can cause such a bright X-ray flux and not vary at these wavelengths?) When astronomers hear about a new catalog of variable stars, the first thing they almost always ask is, "how many periodics?" I spend a lot of time in the paper talking about two "enigmatic" variables with periods of about 42 days; basically after a page or so of babble I get around to saying we don't know what the hell these things are, except that they're interesting and we'd like to know, and that someone needs to try to take more data to figure out what they are. These are their light curves to the left; H and K are the names of the two filters our data are in. (When people started naming their filters back in the day, they gave them sensible names like "b" for the one that let through blue light and "r" for the one that let through red light. The filter just redder of the r-band filter is "i," for infrared, so when the filters started getting further into the infrared they just kept going to j, H, K, L, etc. So K band is redder than H band. And, please, don't think too hard about how the alphabet works right there.) The left-hand panels of the light curves are in days, like the light curve of IRS 10* above; the right-hand panels are phased according the period P so you can see what the light curve is "really" doing.

When astronomers hear about a new catalog of variable stars, the first thing they almost always ask is, "how many periodics?" I spend a lot of time in the paper talking about two "enigmatic" variables with periods of about 42 days; basically after a page or so of babble I get around to saying we don't know what the hell these things are, except that they're interesting and we'd like to know, and that someone needs to try to take more data to figure out what they are. These are their light curves to the left; H and K are the names of the two filters our data are in. (When people started naming their filters back in the day, they gave them sensible names like "b" for the one that let through blue light and "r" for the one that let through red light. The filter just redder of the r-band filter is "i," for infrared, so when the filters started getting further into the infrared they just kept going to j, H, K, L, etc. So K band is redder than H band. And, please, don't think too hard about how the alphabet works right there.) The left-hand panels of the light curves are in days, like the light curve of IRS 10* above; the right-hand panels are phased according the period P so you can see what the light curve is "really" doing.

And just to completely fulfill the promise of this post's title, here are some of my favorite (read: prettiest) light curves from the paper ... for all of these, K band is on top and H band is on the bottom and such, just like before...

I love your curves.

ReplyDeleteMost distracting typo: astronomers here about a new catalog.

Oh, and the dots are on variable stars must mean the red dots.

Typo fixed.

ReplyDeleteWhen I said dots, I meant dots; both the red and the cyan ones are variable stars.

And, by the way Stephen, not only are you not funny, but you're also fairly gross and offensive. Just so you know.

Thanks for the color clarification.

ReplyDeleteNo offense intended. Uhm, the only curves i know about are the graphs. And, sure, humor is in the eye or ear of the audience. Not every joke is funny to everyone. My most inconsistent joke is this one:

So, a Zen Master goes to his hot dog vendor and says, "Make me one with everything."

At least it's short.

This post of yours unexpectedly inspired an observational post on my astronomy blog

ReplyDeletehttp://suitti.livejournal.com/28454.html

I started this blog some time ago, with the idea of humor in astronomy. You know, there'd be some astronomy story, and, there'd be some humor that could happen there. At first, every post had humor. Admittedly, some real life people i know who've read it consider it really strange. But one of my jokes was read on Slacker Astronomy early on, and he cracked up so much that he couldn't get through it. Maybe i should have submitted an audio clip.

Warning, i'm encouraged by both positive and negative comments.