Peanut Star

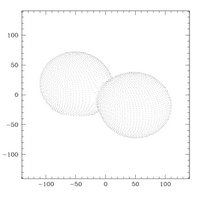

If this star weren't already named "GCIRS 16SW," I would christen it the Peanut Star. Like a peanut, this star has two nuclei (technically, individual stars, but for some reason astronomers say that the two stars in a binary system form a (single) binary star). The two stars are really really close to one another; so close, in fact, that they share material and have a "common envelope," which you can think of as the peanut's shell. Oh, and they're really big: each one is about 50 times as massive as the Sun with a radius about 60 times as large as the Sun's radius. That's freaking huge, by the way. (The axes in this model on the right are in units of the radius of the Sun.) You can count on one hand (without even resorting to counting in binary) the known number of stars in binary systems with comparable masses.

If this star weren't already named "GCIRS 16SW," I would christen it the Peanut Star. Like a peanut, this star has two nuclei (technically, individual stars, but for some reason astronomers say that the two stars in a binary system form a (single) binary star). The two stars are really really close to one another; so close, in fact, that they share material and have a "common envelope," which you can think of as the peanut's shell. Oh, and they're really big: each one is about 50 times as massive as the Sun with a radius about 60 times as large as the Sun's radius. That's freaking huge, by the way. (The axes in this model on the right are in units of the radius of the Sun.) You can count on one hand (without even resorting to counting in binary) the known number of stars in binary systems with comparable masses. The aspect of this particular star system that makes it so interesting is the "GC" in "GCIRS 16SW." GC stands for Galactic center; specifically, our Peanut Star is only about a fifth of a light year (that's about 12,000 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun) away from the massive black hole, Sagitarius A*, at the center of the Milky Way. (In the picture on the left, the yellow arrows are pointing at Sgr A*, and the green arrow is pointing at IRS16SW.) For comparison, the star nearest our own Sun is about 4.2 light years away. While there is a lot of other evidence for really massive stars near the Galactic center, astronomers still don't know exactly how they got there. Massive stars don't live for very long, which means that either they were born frighteningly close to the big black hole, or they were born slightly further away and somehow got transported really close in very quickly. The problem with these stars being born so close to the black hole itself is that stars are usually born in a cloud of cold gas: the gas has to be cold so that it will collapse and get dense enough to form stars. But the gas near the black hole is moving really fast: it's not cold! Lots of ideas trying to solve this dilemma have been put forward, but so far, there isn't one terribly convincing explanation.

The aspect of this particular star system that makes it so interesting is the "GC" in "GCIRS 16SW." GC stands for Galactic center; specifically, our Peanut Star is only about a fifth of a light year (that's about 12,000 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun) away from the massive black hole, Sagitarius A*, at the center of the Milky Way. (In the picture on the left, the yellow arrows are pointing at Sgr A*, and the green arrow is pointing at IRS16SW.) For comparison, the star nearest our own Sun is about 4.2 light years away. While there is a lot of other evidence for really massive stars near the Galactic center, astronomers still don't know exactly how they got there. Massive stars don't live for very long, which means that either they were born frighteningly close to the big black hole, or they were born slightly further away and somehow got transported really close in very quickly. The problem with these stars being born so close to the black hole itself is that stars are usually born in a cloud of cold gas: the gas has to be cold so that it will collapse and get dense enough to form stars. But the gas near the black hole is moving really fast: it's not cold! Lots of ideas trying to solve this dilemma have been put forward, but so far, there isn't one terribly convincing explanation.

By the way, the short paper all about this object that I've been working on recently showed up on astro-ph today.

1 comment:

Just wanted to let you know that this post has been included in the third installment of the Philosophia Naturalis blog carnival (dedicated to the physical sciences and technology). You can see it all here:

http://geekcounterpoint.net/files/GC046B.html

Lorne Ipsum

Chief Geek, Geek Counterpoint blog & podcast

Post a Comment